Dead Angle: Institutions

All around the world, institutions are under pressure—from universities and parliaments to libraries and botanical gardens, the places where power, knowledge, and community are constantly being negotiated. Sometimes they embody their ideals, sometimes their limitations, and often they expose a society’s ‘dead angles’.

The focus program Dead Angle: Institutions brings together films that make these arenas of tension palpable: from the American campus where free-market economics is undermining democratic ideals, to the library in Nairobi that has been freed from colonial legacies, and the seeds returning to Peru after being stored in Madrid for many centuries. In these instances, documentary film acts as both a magnifier and a mirror, showing both the vulnerability and the resilience of the structures that support our community.

“History is therefore never history, but history-for,” a young person reads aloud from a piece of paper. He is perched on the edge of a memorial tablet in the Botanical Gardens in Madrid, filmed on a quiet day. The chirping of crickets blends with the whispering of sprinklers. An idyllic paradise, it seems—but there is nothing untamed or unrestrained about this scene. Every tree and bush has been painstakingly placed; the gardens were laid out with what was then considered scientific precision.

This opening scene from the Peruvian film essay Estados generales (2025) by Mauricio Freyre is, of course, quoting the famous words of Belgian-French cultural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, from his book La pensée sauvage (1961, translated into English as The Savage Mind in 1966 and as Wild Thought in 2021). There, Lévi-Strauss proposes a concept of history that is neither finite nor definite, but dynamic and human—and in which every attempt to write history is inevitably seen through the lens of its own time.

Estados Generales is one of some twenty films made between 1965 and 2025 selected for the themed program Dead Angle, in which IDFA uses documentary cinema to reveal what remains outside our direct field of vision. Many of the films included in the program belong to an observational tradition. The effect is mesmerizing, particularly in the context of institutions: you can only start to recognize patterns and habits, hidden structures, power dynamics, and hierarchies after you’ve spent a long time watching them.

How to Build a Library

After last year’s first installment of Dead Angle, which focused on Borders, this year’s program places institutions in the spotlight—institutions as embodiments of the systems that structure a society. Botanical gardens are a prime example—technically, a science-based collection of plants—which, like modern libraries and art collections, often originated in colonial practices. Today, their collections and archives are being reexamined to reveal what systems of knowledge and histories they truly represent. As the film progresses, we bear witness to the return journey of a small package of seeds that, in the eighteenth century, was transported from what we now call Peru to Spain; finally, they are allowed to return to the soil they were plundered from all those centuries ago.

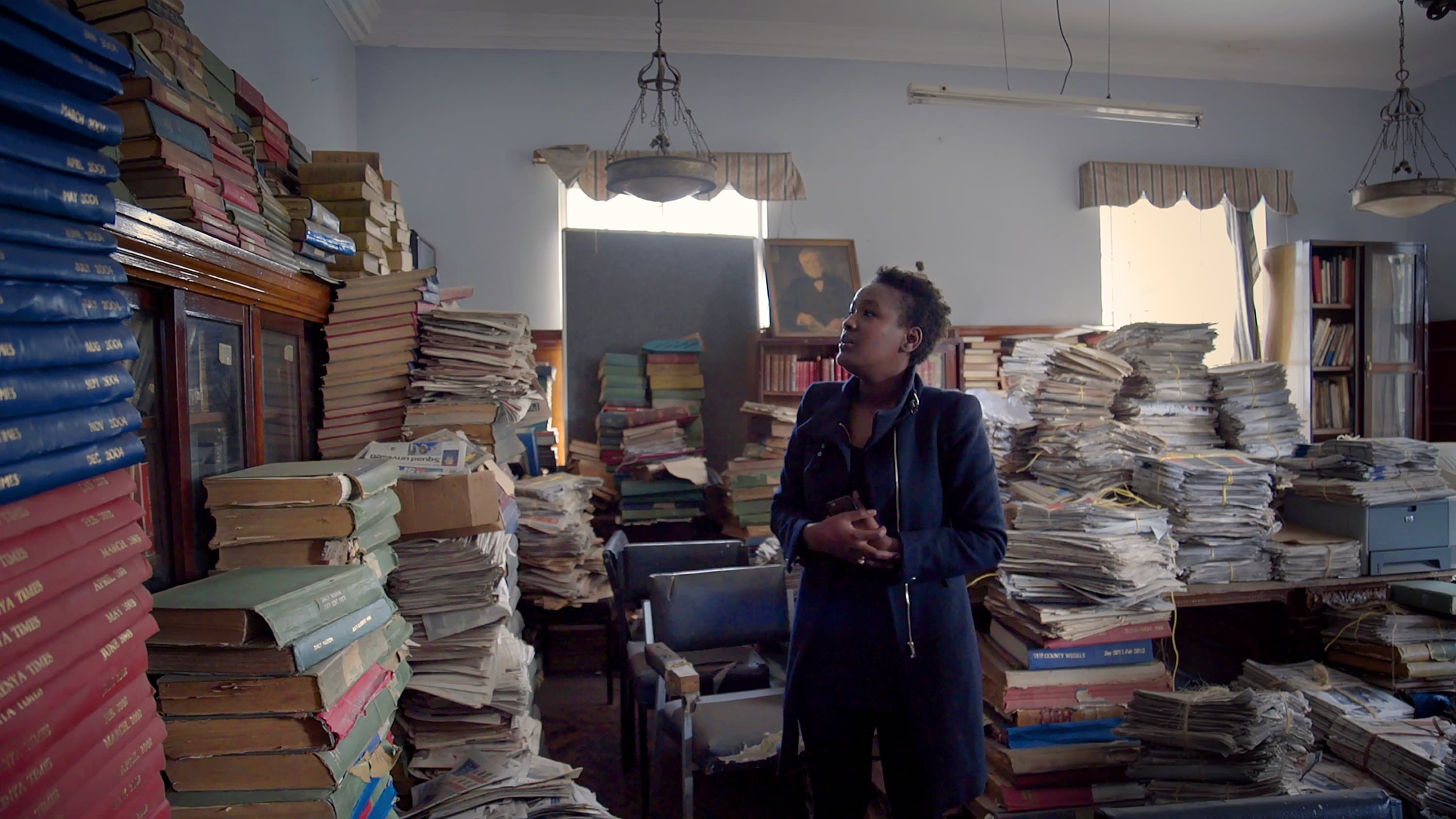

The Kenian film How to Build a Library (2025) by Maia Lekow and Christopher King presents a similar decolonizing perspective. It follows writer Shiro Koinange and publisher Angela Wachuka in their attempts to transform a library in Nairobi, built in 1931 by British-American colonists, into an inclusive communal space. Scenes on cataloguing and classification methods reveal just how deeply colonial structures are embedded in institutions. The library is organized according to the Dewey Decimal Classification system: a numerical framework used predominantly in Western, English-speaking libraries. But classification is never a neutral act; it reflects a particular worldview. It defines what is included and excluded—which can even include entire languages, as the film reveals.

Yet liberating yourself from entrenched power dynamics is no simple matter. When a senator is invited to the library’s opening but the governor is not, we get a sharp insight into the protocols, traditions, codes, and behavioral patterns that safeguard institutions—but also the rigidity that can stifle them. This is a process European cultural institutions—including IDFA—have grappled with first-hand in recent years.

Frederick Wiseman’s films make comparable observations, but within American and European contexts. Barely five minutes into At Berkeley (2013), the ideals of the University of California, Berkeley are already colliding with reality. In a lecture hall, an audience listens to the university’s origin myth, dating back to its founding in 1868. It’s a good story. Towards the end of the California Gold Rush in the mid nineteenth century, two professional gamblers and a saloon owner, after drinking a fair amount of alcohol, decided to set up a university. Even if not fabricated, the lecturer argues, the tale reveals something important. From the outset, Berkeley cherished an ideal: the institution aspired to be accessible to those outside the elite, unlike other major American universities, such as Harvard and Yale.

The film then cuts to another meeting room, as if both conversations are taking place simultaneously. Here, impending budget cuts are on the table. On the one hand, there is pride in not relying too heavily on government funding; on the other, private investors bring private demands, while state support had once ensured that the university could remain accessible, inclusive, and independent. At least, within a political system designed to guarantee it. Through legislation and traditions, through all the written and unwritten rules that underpin society. If At Berkeley demonstrates anything, it is that once the market gains influence, everything risks becoming a product. The film shows how the institution gradually succumbs. Even a decade ago, the university seemed as idyllic as Madrid’s botanical gardens. But the idyll was deceptive: a small ecosystem with its own infrastructure and currency, where democracy revealed itself in meetings and participatory bodies.

Since Wiseman made his film in 2013, the world has changed. This American university has taken on a symbolic role larger than itself. In the summer of 2025, US president Donald Trump announced plans to impose a billion-dollar fine on Berkeley for pro-Palestinian protests on its campus. Trump and his allies are not only attacking a symbol, but also a history.

Of course, this phenomenon is not limited to the United States. All over the world, populist and authoritarian politicians are channeling their frustration with the complex problems that cannot be solved within the borders of the nation state—from the climate crisis to globally entangled wars and genocides—into systematic attacks on national institutions. Science, a free press, and independent judiciary are suffering from this just as much as cultural institutions.

Cover-Up

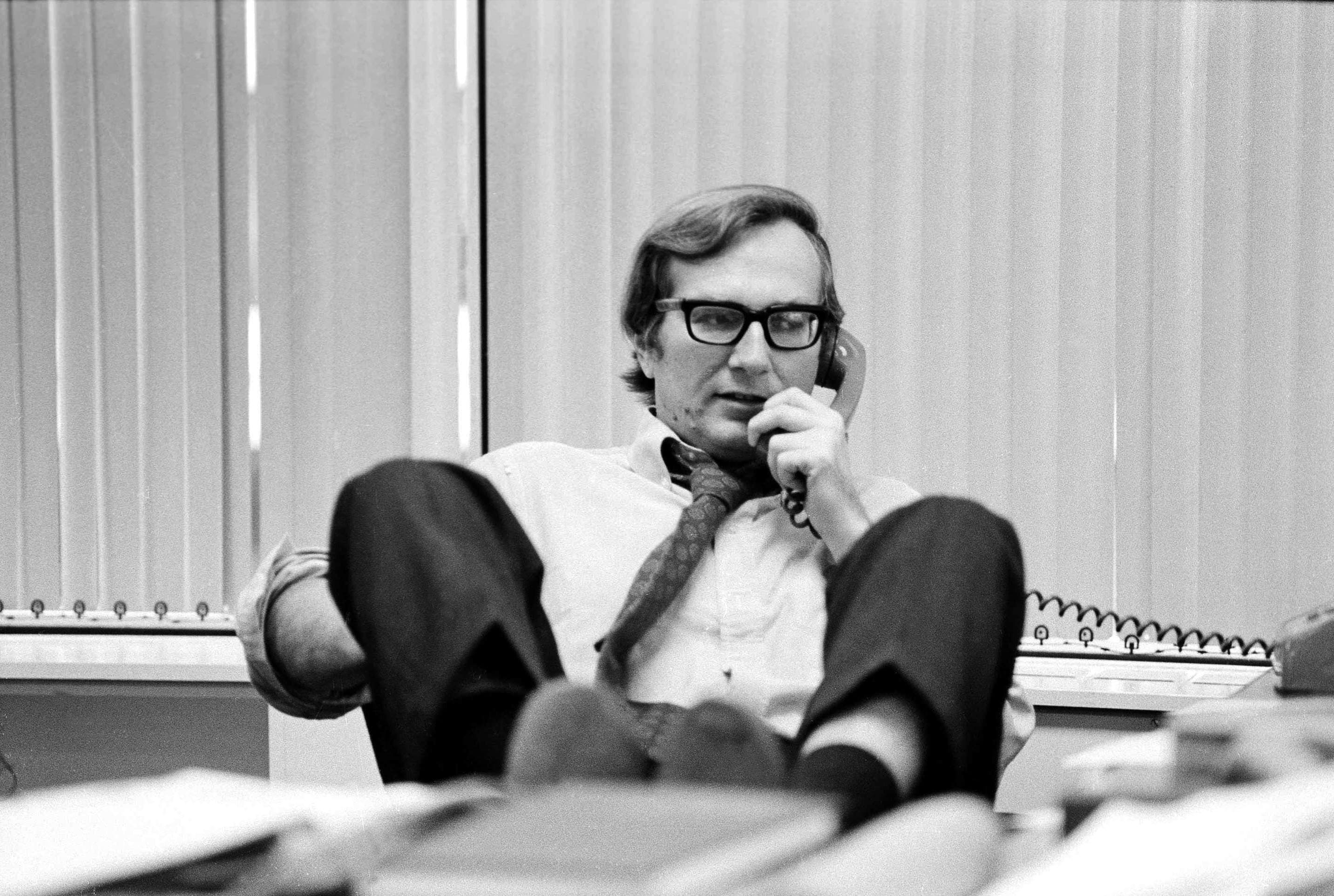

In Laura Poitras’s latest film Cover-Up (2025), about American journalist Seymour Hersch, the filmmaker also draws many parallels with the 1960s. Investigative journalist Hersch became famous for exposing the Mỹ Lai massacre—the mass murder of the civil population of a South Vietnamese village by US troops—and its subsequent cover-up. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1969 for his exposé.

Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, who has previously produced TV programs with Hersch, interweave Hersch’s revelations with a long interview in which they try to grill him about a journalist’s most important tool: their sources. It’s breathtaking to see how the interviewer gradually becomes the interviewee, and how sensitive some of the topics remain. Can a journalist become an institution themselves? And if so, who holds them to account? Can you get too close to power if you’ve built your career on sources within the armed forces and intelligence services? At the same time, Hersch is still breaking news; his ongoing research into Gaza is a time bomb hidden within the film.

In the same year Hersch received his Pulitzer, French philosopher Michel Foucault published his book The Archaeology of Knowledge, in which he argued that what we might like to see as objective knowledge (and institutions) never exists outside the influence of power structures. Contemporary feminist philosopher Sara Ahmed is one of the thinkers also expanded on these power structures from an intersectional perspective.

This is also the approach taken by the oldest film in the program: Toute la mémoire du monde (1956) by Alain Resnais. This short documentary is a poetic-literary film on the National Library of France in Paris, presented as a monumental archive of knowledge. Yet between the images, Resnais also exposes the limitations and biases inherent to the systems of classification.

exergue – on documenta 14

If this selection of films makes one thing clear, it’s that—to paraphrase the title of philosopher and filmmaker Astra Taylor’s book on democracy—the perfect institution doesn’t exist and is never finished, but we will still miss them when they’re gone.

exergue – on documenta 14 (2024), by documenta’s “in-house cinematographer” Dimitris Athiridis, offers more than fourteen hours of behind-the-scenes footage from the 2017 edition of documenta. Held simultaneously in Kassel and Athens, the exhibition was marked by financial and logistical problems, as well as controversies. And this was before documenta 15 came under fire over allegations of antisemitism and the challenges posed by the Indonesian collective ruangrupa, serving as guest curators with a radically global and collective curatorial vision.

exergue is as ambitious as documenta 14 itself. It exemplifies the ways in which cultural institutions—including IDFA—have had to account for and reinvent themselves over the past decade. This makes the film at once revelatory and shocking, while also serving as a warning against building new Biblical Towers of Babel—whether these are libraries, online archives, or traditions set in stone—which, sooner or later, will lead to a Babylonian confusion of tongues.

This editorial was published in the IDFA 2025 Program Guide.

See the full Program Guide here.