DocLab is off the internet

The 19th edition of IDFA’s new media program DocLab revolves around the relationship between the digital and the physical world. Is DocLab now off the internet, or is the entire world now on the internet—annexed by tech companies whose utopias have spun totally out of control?

This article appeared earlier in the IDFA 2025 Program Guide.

“I’ve spent my entire life at a computer,” artist Jeroen van Loon recounts passionately during a TEDx talk in 2024. All was fine—until 2010, when, on the verge of graduating, his whole body began to hurt whenever he came close to a computer. Not exactly convenient when you’re studying Digital Media Design. So, he decided to turn this disadvantage to his advantage, and designed the project From Digital to Analogue (2010): a “digital exile experiment” that involved him staying away from his computer for two months.

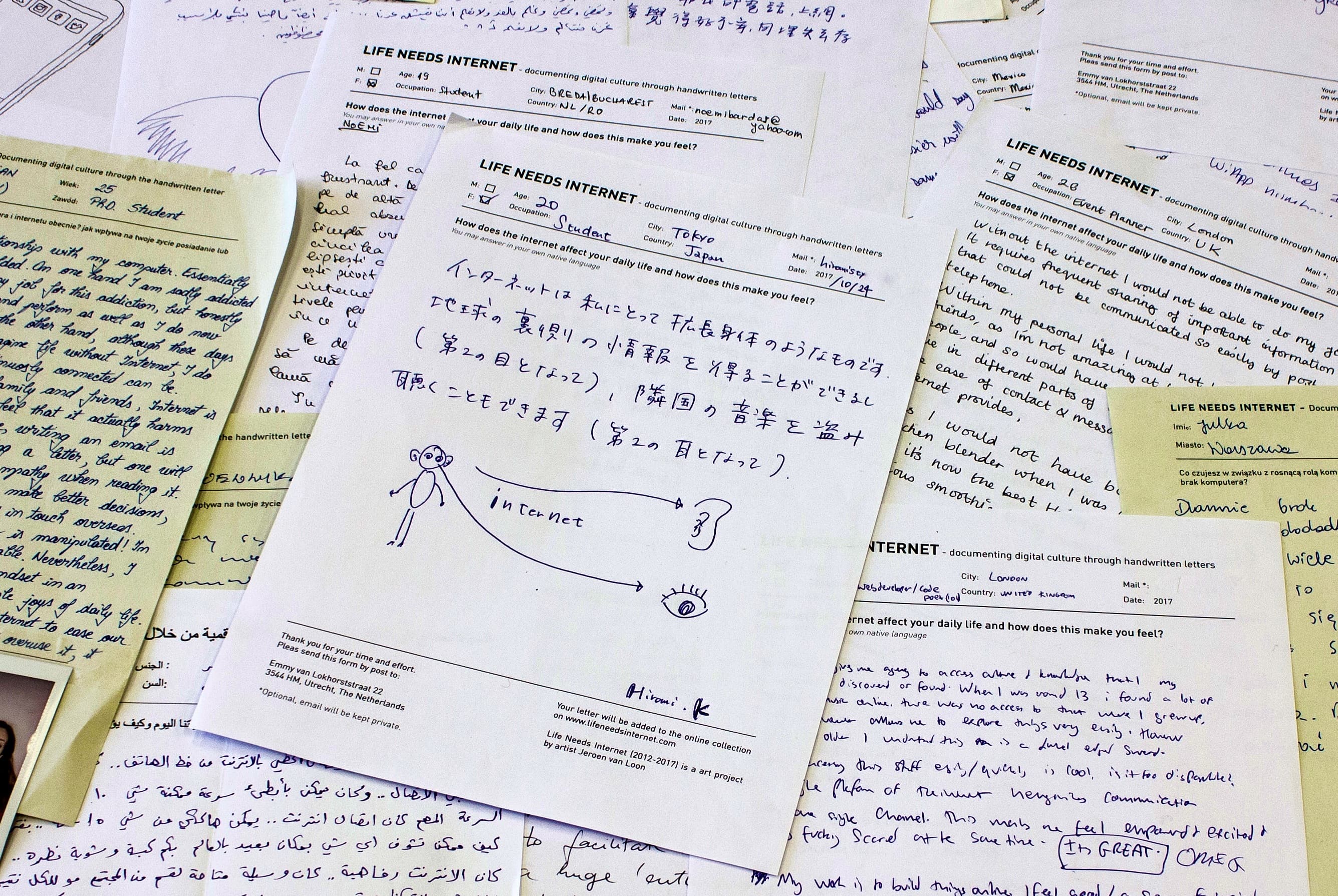

He is exhibiting a series of handwritten letters, paired with video portraits, collected from people all over the world: from Brazil to Ghana, from France to West Papua. Through his website, Van Loon asks participants to write down their thoughts about the internet on paper. In the early years, some contributors had little experience with computers or the worldwide web, which makes the collection all the more revealing. Over fifteen years, the archive has grown into a cross-section of the accumulated strata of our digital lives. Life Needs Internet 2010–2025, the long-term project Van Loon is presenting during IDFA DocLab 2025, can be seen as the culmination of his offline investigations.

Life Needs Internet 2010–2025 by Jeroen van Loon (2025)

Life Needs Internet is a fitting introduction to this year’s IDFA DocLab program. Programmers Caspar Sonnen and Nina van Doren have chosen the umbrella theme Off the Internet: this can be interpreted as an encouragement, a question, and a conclusion. Getting off the internet is something we increasingly hear people talk about in 2025, as we find ourselves surrounded by digital detoxes and apps that are (ironically enough) designed to limit our screen time. The title also carries a double meaning, questioning the extent to which documentary digital media art is ‘of’ the internet: how much do we owe to the internet at large? Another pressing issue is that artworks are increasingly being used as training data for the big tech companies. Artists are trying to take control by building their own closed systems, which often work offline, to avoid feeding their data into AI systems controlled by these companies.

It’s no coincidence that the name IDFA DocLab contains the word Lab (laboratory): for almost two decades now, this has been the natural home for documentary art that makes use of digital, immersive, and spatial narrative forms. Anyone who’s been to DocLab knows it’s more than just a showcase for the annual crop of XR documentaries. Each program is created in dialogue with makers who interrogate their medium. From the start, DocLab has shown that many digital artists are, paradoxically, exploring what it means to go offline. Following previous themes including Phenomenal Friction (2023) and This Is Not a Simulation (2024), the call to bridge digital and physical realities has been building for some time. Real-world issues such as the climate crisis (every prompt is equivalent to a bottle of mineral water) and the relationships between tech companies and the arms industry can no longer be waved away.

Caspar Sonnen - Head of IDFA New Media“For a long time, I believed that Big Tech didn’t care about the arts. Why don’t we have an app for looking at art on your phone? But, of course, you can also flip the question: should you want to look at art on your phone?”

“What’s more, the program’s subtitle ‘celebrating art in physical space’ also refers to the origin story of DocLab,” Sonnen says. “It’s about bringing together these, at the time, elusive forms of digital documentaries and extended realities—along with the communities surrounding them—in a physical space.” In the years ahead, through the research program Shared Realities, DocLab will explore how archiving and a shared infrastructure for these communities could be developed. “We’ve built a fantastic catalogue of works that can serve as reference material for everyone, even though many of them are poorly described or hard to find. For a long time, I believed that Big Tech didn’t care about the arts. Why don’t we have an app for looking at art on your phone? But, of course, you can also flip the question: should you want to look at art on your phone? Doesn’t immersive and digital art off er possibilities far beyond what a smartphone can provide?”

This is why Flemish production house Ontroerend Goed has decided to go completely offline. Handle with Care (2025) opens with a box in the middle of the performance space. No actors. Nothing else. The show starts the moment someone from the audience gets up and opens the box, which contains instructions for them to perform the show themselves. By the end, the company hopes participants will have answered the question: Can a theater company ‘produce a show’ without ever being present?

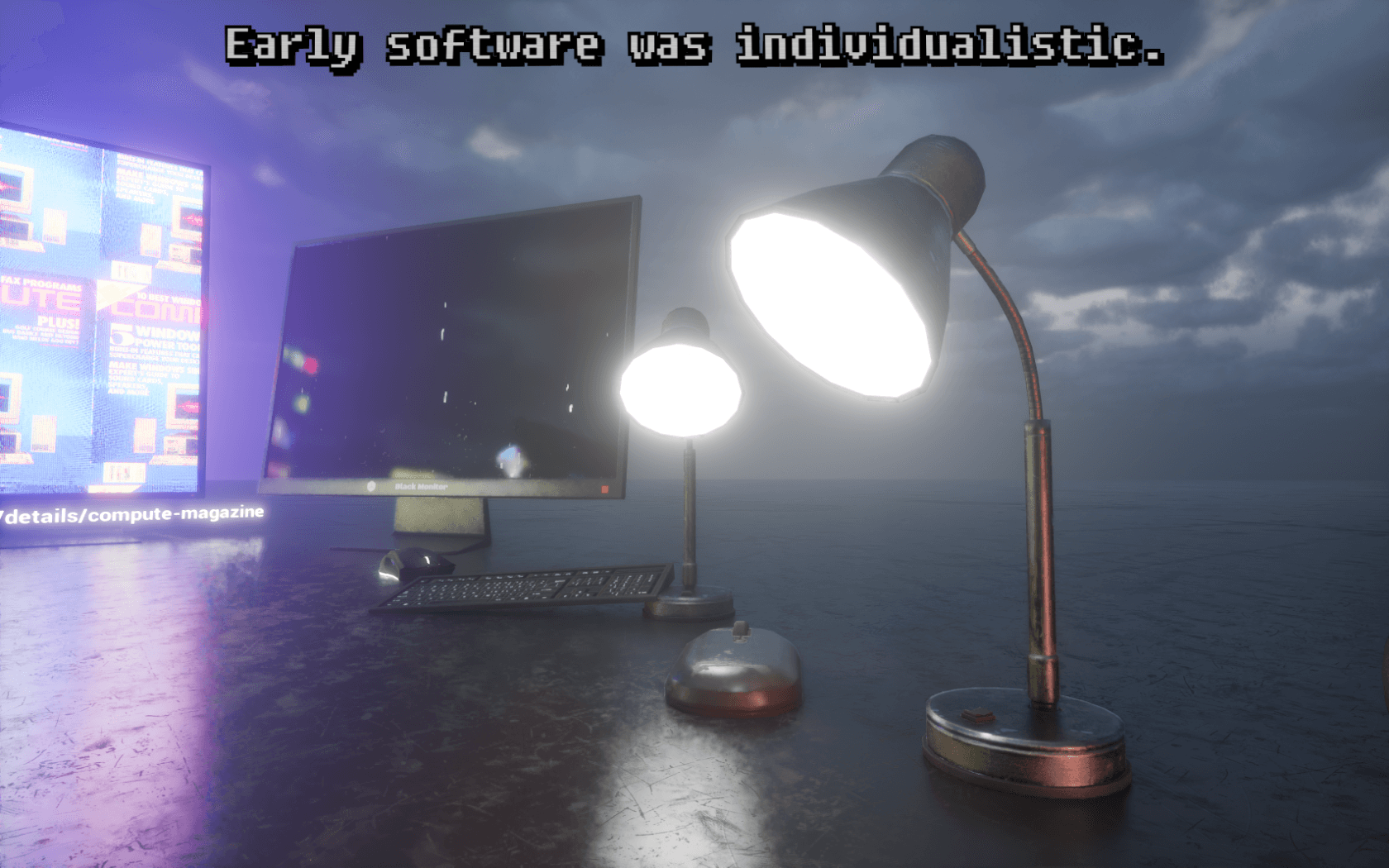

individualism in the dead-internet age by Nathalie Lawhead (2024)

Internet culture from a decolonized perspective is central to the musical Feedback VR, un musical antifuturista (2025) by Claudix Vanesix / Collective AMiXR. The collective takes its name from the Latin-American hi5 culture: a social network where people communicate with an urban-digital language in which sYmB0l$ (symbols) are used to cH4ng£ w0rD$ (change words). They describe Feedback as a psychotropic trip, bending half-rendered images and radical performances that catapult Peruvian traditions and stories into a parallel universe—a striking digital form of Indigenous futurism.

Another work that probes “platform decay” is Individualism in the dead internet age: an anti-big tech asset flip shovelware rant manifesto (2024) by Nathalie Lawhead, a marvelous walkthrough of a digital churchyard. The term “platform decay” has gained traction recently, in the wake of Cory Doctorow’s recently published book Enshittification, in which he analyses how misogyny, conspiracy theories (the “dead internet” is one of these), surveillance, manipulation, fraud, and AI garbage have polluted the internet. First, a platform lures users with free content; then it monetizes the activity, attracting paying customers while degrading the user experience; finally, every last ounce of shareholder value is extracted from the platform.

This phenomenon aligns with what social media researcher danah boyd calls “context collapse”: endless sharing, linking, decontextualizing and forwarding of content blurs the line between the original senders and recipients. As a result, someone’s news feed can juxtapose posts about the genocide in Gaza with advertisements or AI-generated cats. Nowhere is the power of immersive media more evident than in the VR project Under the Same Sky (2024) by Khalil Ashawi, Sami Sultan, and Hadil Arja. This 45-minute 360° video, created by citizen journalists working inside Gaza, places viewers directly in the midst of daily life. Through the spatial awareness of VR, the project fosters a sense of immediacy and presence that traditional media often cannot convey, offering a profound antidote to the disjointed, context-collapsed feeds that dominate online experiences.

Feedback VR, un musical antifuturista by Claudix Vanesix / Collective AMiXR (2025)

Finally, Celine Daemen—who in her previous works Euridyce (2022), a descent into infinity and Songs for a Passerby (2023) treated the virtual world as a playground for philosophical questions about the nature of reality—takes us on a deep dive into a parallel universe. The international success of her work has also boosted the visibility of the XR scene in the Netherlands. Nothing To See Here (2025) premieres at DocLab: an interactive installation made for public space that, at first glance, resembles one of those stereoscopic diorama boxes in museums, offering a glimpse into another reality.

Daemen sends us tumbling deep into a mirror of our own reality. We see ourselves, impossibly far way, staring into this box. We recognize the ceiling above us, but the proportions are askew. People walk past us who we cannot see beside us. Are we our own doppelganger? Are we trapped in a virtual world? Daemen and her team have created an optical and sonic illusion that links the early days of cinema to contemporary digital chaos. It turns out that we can inhabit two worlds at once— alongside others.

The Oracle: Ritual for the Future (for humans and non-humans) by Victorine van Alphen (2025)

IDFA DocLab is made possible by: Ministerie van Economische Zaken, Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap, Creative Europe Media, CLICKNL, Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie, Creative Industries Immersive Impact Coalition, Nederlands Filmfonds, Agog and IDFA Special Friends+.

DocLab's research collaborators are Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences, ARTIS-Planetarium, Beeld & Geluid, Diversion cinema, Droog, Onassis ONX, PHI, Vlaams Cultuurhuis de Brakke Grond, Voices of VR and We Make VR.