Shaking up the Youth Competition: Niki Padidar’s fresh approach

Over the past few decades, there’s been a noticeable shift in how youth films portray young people and what they’re believed to be capable of.

Once known for its bold, experimental storytelling the genre now seems to have taken a safer, sometimes even more conservative route. That adventurous spark, which once drew children in and introduced them to the complexities of the world, has faded. This is why Niki Padidar, a filmmaker and now in her second year as curator of IDFA’s Youth Competition, is charting a new course.

“Over time, certain restrictive patterns have developed that filmmakers and producers feel they have to follow,” Padidar explains. “A lot of films over-explain things. Everything is spelled out, and there’s no room left for imagination. But young audiences are actually incredibly capable of thinking for themselves and drawing connections.” She believes this underestimates kids’ intelligence. “Films that leave them with a sense of wonder, or even confusion, can be far more engaging for young viewers,” she says. Instead of predictable storytelling, she wants films to spark curiosity—and sometimes even provoke a little discomfort—encouraging children to make sense of what they’ve seen for themselves. “That’s when they start questioning their own understanding of the world, instead of constantly seeing it affirmed. You don’t learn from that, and it certainly doesn’t broaden your perspective.”

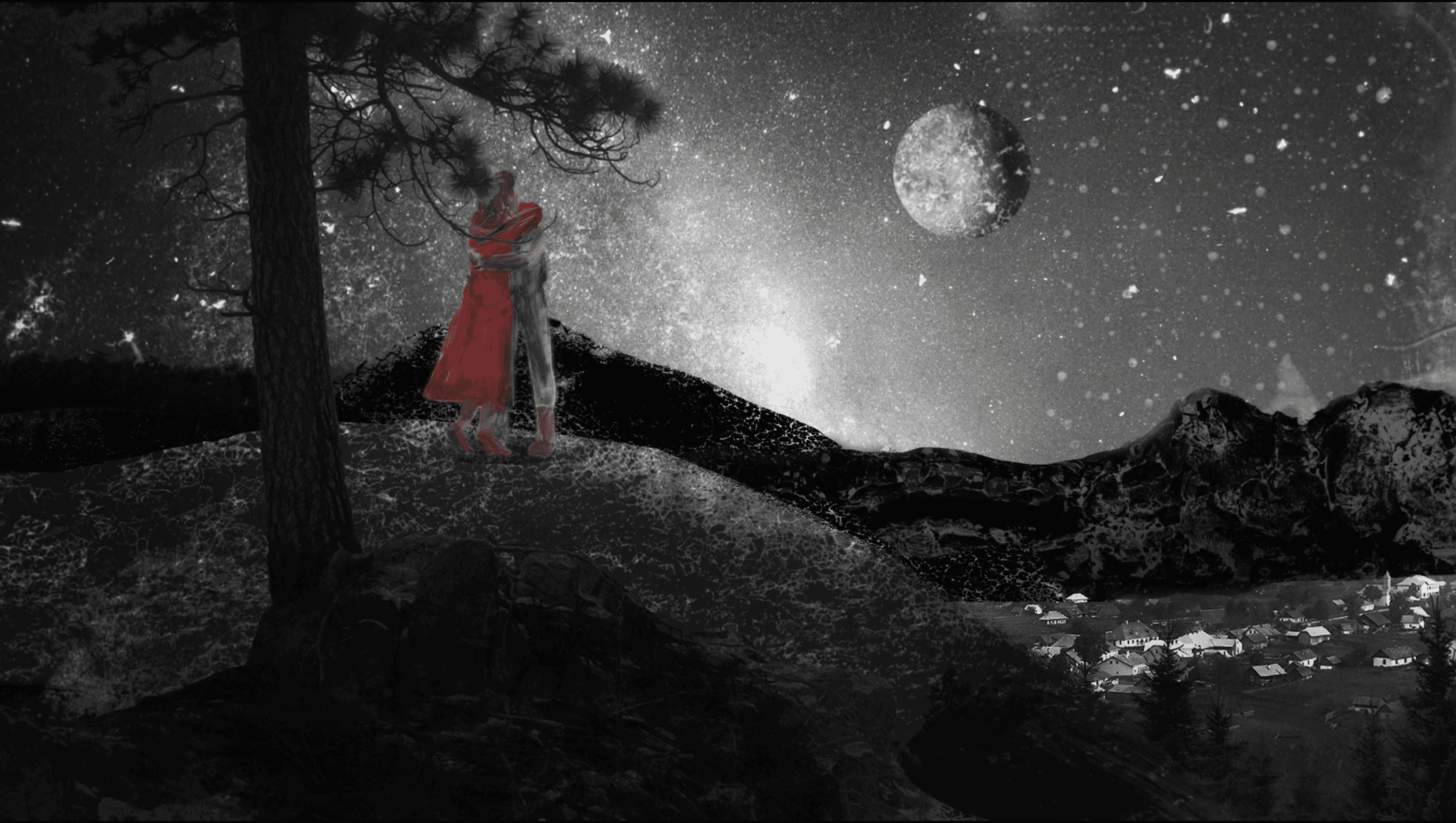

Still from Crushed (2024), dir. Camille Vigny

That’s why Padidar has cast a wider net, looking for films that, while not originally submitted as ‘youth films,’ still have something valuable to offer young audiences. She seeks stories where young protagonists are portrayed with depth, rather than being reduced to a single trait or mission. “One of the biggest pitfalls in youth films is the tendency to flatten characters and themes,” she explains. “You see it with a transgender character whose story revolves solely around their transition, as if that’s all there is to them. Or a film about a drug addict who’s only ever shown causing pain to their loved ones. Or a Kenyan family portrayed purely through the lens of poverty, with no room for scenes of their everyday lives.” For Padidar, the best films show people as they really are—complex, with conflicting emotions and behaviors.

On the other hand, youth films too often fall into black-and-white thinking, exaggerating the divide between good and evil, ‘us’ and ‘them,’ as if young audiences can’t grasp more nuanced ideas. But this approach only reinforces stereotypes. “What we should be doing,” Padidar argues, “is helping kids understand that the world is far more complex. Films that resort to simplistic storytelling don’t prepare children to navigate that complexity—they just reinforce biases and encourage a more polarized view.”

“That’s one the reasons why many of the films in IDFA’s Youth Competition follow less traditional, more unpredictable storylines,” she continues. “Take Crushed by Camille Vigny, for example. It follows 18-year-old Camille as she falls in love, only for the relationship to turn possessive and violent. This kind of story flips the usual happy-ending narrative on its head, reflecting a much more realistic scenario.”

Another film Padidar highlights is A Place to Call Home by Parisa Aminolahi, which follows a father and his two daughters in a beautiful yet subtly unsettling environment. There’s an underlying sense that something isn’t quite right. Through fragmented conversations, we gradually learn that the family has left something important behind and is now searching for a new place to call home. “It’s a fresh take on what could easily have fallen into the category of a ‘typical’ refugee story,” she says.

A Place to Call (2024, dir. Parisa Aminolahi)

The Youth Competition is designed to be anything but conventional. “We’re aiming for a broad range of styles, both in terms of storytelling and visual language,” Padidar explains. “This could mean an absurdist animation like last year’s Headprickles, or a more meditative short film like this year's The Flower by the Road, which leaves things open to interpretation without a rigid narrative.” For this reason, she collaborates closely with colleagues from the Shorts Competition, as their entries often challenge the boundaries of what documentary can be. “That’s exactly the kind of risk-taking we want to encourage.”

Visitors will be treated to a carefully curated program that often pairs two or more films together, with one being a little more challenging. “If people leave thinking, ‘What on earth did I just watch?’ I’d prefer that over a film that makes no lasting impression. Think back to the films and shows that impacted you as a kid—were they the safe, predictable ones?”